Return

to Breed Profiles Main Page Banker HorsesBy Donna Campbell SmithNorth Carolina's Outer Banks is home to about four hundred wild horses that roam free in some parts of this popular resort area. The Banker horse is a tough breed that has survived hurricanes, scorching heat, bloodthirsty insects, and winter storms while living on coarse sea grasses and digging in the sand for fresh water. They are descendents of horses brought to the islands centuries ago by Spanish explorers. Columbus brought horses to the New World and set up breeding ranches in Hispaniola in the late 1400s. Rather than transport horses and their food across the Atlantic, European explorers purchased horses from the Hispaniola ranches to use on their explorations of the mainland.

Luis Vazquez de Ayllon sent three expeditions from Toledo, Spain to explore the Carolina coast. Records show he brought five hundred men, women, children, slaves and ninety horses in an attempt to establish a colony. Ayllon and many of the colonists died of fever. The survivors returned to Hispaniola, leaving their horses and livestock behind. Other explorers who came and then left in a hurry because of harsh conditions, sickness and poor relations with the Native People repeated this scenario. The horses were considered disposable transportation, not worth the time or expense to take back home.

The horses not only survived, they flourished on the string of barrier islands until, by the 1950s they numbered in the thousands. They were used for transportation of people and supplies, they helped pull in fishing nets, plowed family gardens, and carried midwives on their rounds.

North Carolina's development depended heavily on the Banker horses. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries they were considered an important economic commodity. Regular roundups were held on the islands, called pony pennings. The Bankers were auctioned off to buyers from the mainland who valued them for their heartiness. The physical characteristics of the Banker are very similar to many Spanish breeds. These horses are compact in size, usually 14 -15.2 hands high and weigh about 800-1000 pounds. They have broad foreheads with a straight or slightly convex profile, short backs, strong croups with high to medium-low tail sets, and long silky manes and tails. Many Banker horses are gaited. Dr. D. Phillip Sponenberg, who has done extensive research on the wild horses of the east coast writes, "These horses usually have a very long stride, and many of them have gaits other than the usual trot of most breeds. These other gaits can include a running walk, single foot, amble, pace and the paso gaits of other more southerly strains." (The North American Colonial Horse)

In old writings about the Bankers they are often described as "smooth gaited." According to the report, "Genetic Analysis of the Feral Horse Populations of the Outer Banks" written by Gus Cothran, Ph. D. from the University of Kentucky, "Corolla herd has only 29 alleles, among the lowest number of any horse population." That means there is less genetic diversity among the Corolla group than any other group of horses. Rather than being feral horses with a mixture of domestic breeds, "they are in effect "a breed unto themselves." This is probably due to their isolation and inbreeding, but when compared to other breeds the Corolla herd's DNA tests show they closely resemble the old Iberian horses.

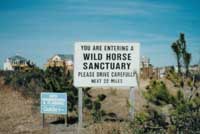

The northernmost town of Corolla existed in peaceful harmony with their wild horses for centuries. When the small village became a bustling vacation center in the 1980s, with condos, shopping centers, restaurants and ritzy beach houses, the horses' future was endangered. With a new highway came traffic; and in the first year of the highway opening seven horses were struck by cars and killed. Townspeople organized the Corolla Wild Horse Fund and immediately put into action a carefully thought out management plan. They moved the herd to a less inhabited part of the islands where it is maintained at about sixty horses to protect the ecological balance of the area. It is also the job of the group to prevent horses from accessing the developed areas, and to relocate any "rogue" horses that stray back into town or other private sites. Another herd lives one hundred miles south of Corolla on Ocracoke Island. These horses no longer roam free, but are under the care and management of the National Park Service, since the island is part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Tourists can safely "pony watch" from the observation tower next to the fenced pasture. Park rangers sometimes ride Banker horses while they are on beach patrol, after the tradition of the US Life-Saving Service surf-men of the 1800s. In fact, North Carolina's surfmen were the only ones in the country allowed to ride, rather than patrol on foot. This was because nearly everyone on the Outer Banks had their own Banker horse. They didn't cost the service anything, and the surfmen could do a better job on horseback.

Several other small islands have small groups of Banker horses. Called marsh tackies or sand ponies by the old timers who share the islands with them, the horses graze in the outlying marshes. The horses have an uncanny ability to move through the mud and mire with ease. The largest herd of free-roaming wild horses in the state, with about one hundred, The Foundation for Shackleford Wild Horses organized and they found a friend in Congressman Walter B. Jones, Jr. He introduced a bill to Congress to protect the horses. Now the National Park Service at Cape Lookout National Seashore, in cooperation with the Foundation, manages the Shackleford Herd.

DNA testing helped the Foundation for Shackleford Wild Horses gain their government support. This group has set up a stud-book for establishing the Banker Horse as a breed, registered with the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy. Birth control and adoption are two methods being used to keep the Shackleford herd and its environment healthy. Some of the adopted horses have been put into private breeding programs. Some of the Bankers have also been accepted into the Mustang registry. Still, North Carolinians fear for the future of their Banker horses. It is a constant uphill battle as increasing development encroaches on what was once wilderness land. Even public education is a two-edged sword. There is a need for the public to be aware of the horses, because they provide badly needed funding. But, letting people know about the Banker horses also opens up the possibility of harassment by people in this world who do that kind of thing. Several incidences of abuse, whether out of ignorance or malice, have enraged those who work so hard to protect the horses: a colt was run down and killed by the driver of a SUV on the beach, With their future so uncertain, these hardy little horses can teach us a lot about perseverance and survival in a harsh environment. It is worth pondering the fact that these horses have survived every obstacle nature has sent them for four hundred years, but it is doubtful they can survive man's idea of progress. Corolla Wild Horse Fund Foundation for Shackleford Horses, Inc. About the Author: |